ASCENDANT INFRASTRUCTURES: THE MEGACHURCH AND OTHER EXPANSES

This thesis interrogates the relationship between corporate governance, nationalism, and reactionary ideology and their confluence within the spatial and mediatic typology of the American megachurch. It focuses specifically on James River Church—a megachurch based in Springfield, Missouri, with four campuses, 16,000 weekly attendees, and 1.1 million YouTube subscribers—and the Assemblies of God, a cooperative fellowship and governing body also headquartered in Springfield, which has overseen the planting of over 13,000 churches in the United States and 450,000 globally. To reveal the interrelation of these ideologies, this project aims to draw out the perceived contradictions of the megachurch: on the one hand as a neoliberal architecture that emphasizes flexibility and freedom, observed through the proliferation of flex office spaces, informal gathering spaces, a church sanctuary rented out to secular events, and the capture of its congregants as social and spiritual beings; and on the other hand as a heavily fortified architecture that reflects anxieties of the “other,” read through the use of tinted windows, AI-enhanced security cameras, a full-time security team, and police presence during service times.

To do so, I look at the imaging of broadcast spectacle featuring nationalist and militaristic displays; the iconography of James River Church and Assemblies of God in the form of social media graphics and contract documents that present global aspirations; closed-circuit broadcast imaging through AI-enhanced surveillance cameras used for facial recognition, loitering detection, and smart audio analysis programmed to detect gunshots and other anomalies; and the architecture object itself as an image: a laterally expansive, commercialized space primed for self-replication that functions as a symbolic monument able to be endlessly multiplied within a larger neocolonial network.

In 2017, the eighth triennial World Congress of the Assemblies of God convened at two separate megachurches in Singapore to accommodate the 16,000 people in attendance. Titled “Generations: A Prophetic Legacy,” the congress took place simultaneously at Trinity Christian Centre and Grace Assembly of God. The two campuses were connected via livestream, with a split-screen projection in both sanctuaries, as congregants joined in a technologically mediated prayer over Chairman George O. Wood’s vision: to establish one million Assemblies of God churches by the year 2033. This was called Mission Mandate 33, and was inaugurated with a media campaign depicting images of city skylines and text advocating for global expansion.

Today, on the other side of the world at the Assemblies of God National Office in Springfield, Missouri, a sky bridge is lined with the flags of the 160 constituent nations of the World Assemblies of God Fellowship. The National Office, the headquarters for the Assemblies of God, was constructed in the 1960s and has since housed the administrative and executive offices of the largest Pentecostal denomination in the world. With 13,000 churches in the United States, and 450,000 churches globally, Assemblies of God functions as a corporation and oversees a vast economy of real estate, labor networks, and tax exemptions enabled by a parallel landscape of technology and mass media production.

Within Springfield, Assemblies of God maintains enormous local influence. It oversees several megachurches, including James River Church, the largest Springfield megachurch with four campuses, 16,000 weekly attendees, and 1.1 million YouTube subscribers.

James River Church South (top left), North (top right), West (lower right), and Joplin (lower left) Campuses:

The Assemblies of God also sells investment certificates, issues loans for church planting and the growth of existing churches, mortgage and home equity loans for individuals, credit cards, insurance plans for mission trips, and testamentary planning services contingent on a 10% donation of one’s estate to an Assemblies of God ministry of choice. It also oversees three local universities: Evangel University, Global University, and James River College—each with their own evangelical outreach programs and advertisements.

Map of Springfield showing the distribution of Assemblies of God churches and megachurches:

National governance districts of the Assemblies of God, their megachurches, and 19 affiliated universities:

Participant nations in the World Assemblies of God Fellowship:

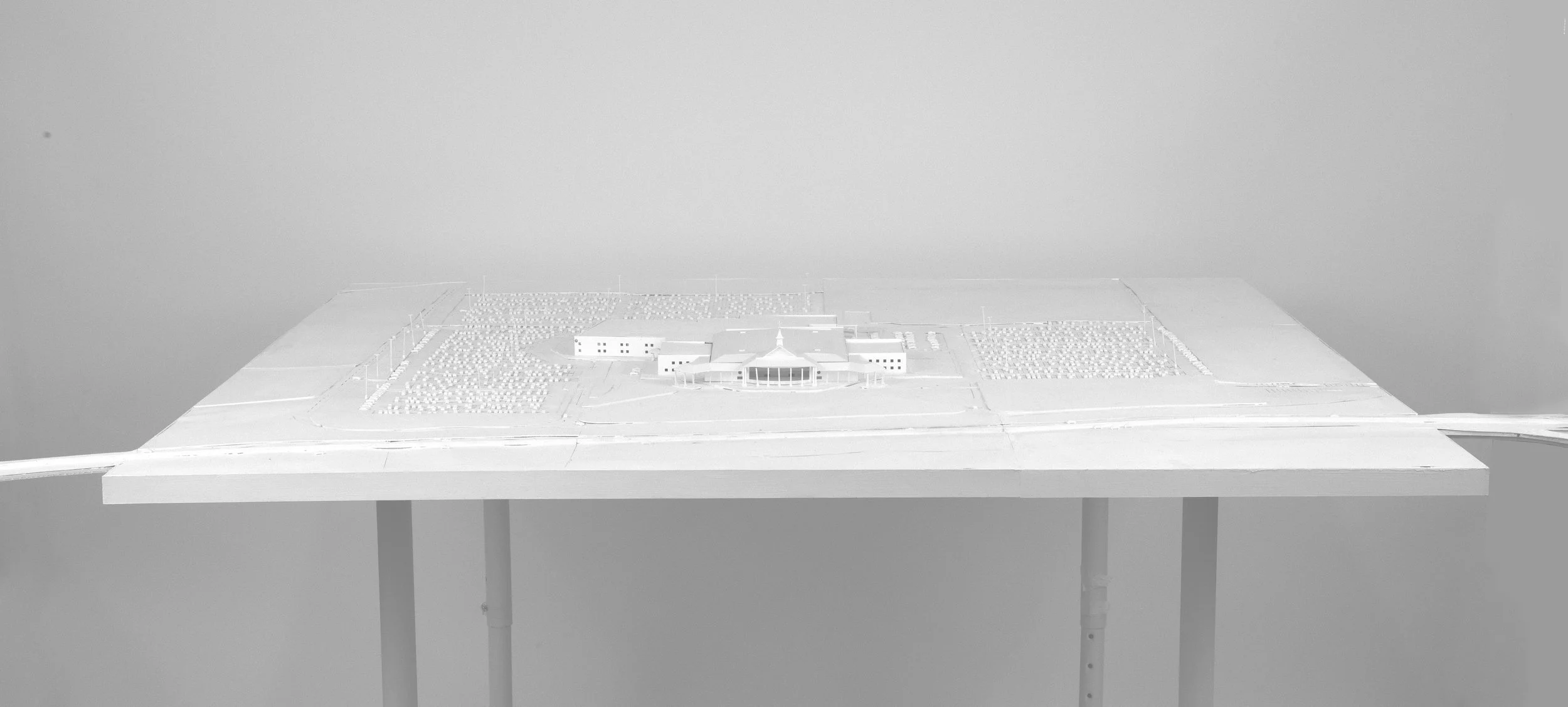

Architecture, within this network, operates both as the foundational product of this economy and as the site through which its consumer base is extracted. The megachurch—laterally expansive, commercialized, primed for self-replication—acts as a symbolic monument able to be endlessly multiplied within a larger neocolonial network that seeks to expropriate land, labor, and capital at the global scale. This thesis intervenes in the seemingly banal infrastructure space of the megachurch through an analysis of the imaging techniques of James River Church and the Assemblies of God— broadcast images both public and closed circuit, contract documents and bylaws, and the image of the expansive architectural footprint of the megachurch. This thesis reveals the interrelation of neoliberalism, corporate governance, nationalism, and development logics central to the megachurch typology.

The ‘healthy church,’ as discussed throughout Assemblies of God media, is one with the ability to grow and flourish under the free market. The “expansion of God’s Kingdom” is predicated on the construction of churches and development projects. Correspondingly, faith healing rituals, with a long history in Pentecostal tradition used to treat injuries and ailments in the human body, are extended to architecture and geographies.

The World Prayer Center, for example, one block away from the National Office, has a 600 square foot LED floor that allows visitors to pray over geographies of their choice—primarily areas associated with Assemblies of God World Missions trips.

Although designed to accommodate thousands, these architectures remain largely empty for most of the week and fail to function as true public institutions, despite presenting themselves as such. The notion of the “outsider” is leveraged to intensify the surveillance and security measures within these spaces. James River Church, for example, employs an AI-enhanced surveillance system programmed for facial recognition, loitering detection, and gunshot detection. It also maintains a visible police presence during services, and 48 its windows are tinted to obscure visibility. The implementation of technologies of threat assessment and anticipatory governance point to the encroachment of carceral logics within the contemporary church typology — logics seemingly at odds with the neoliberal image of flexibility and freedom the megachurch attempts to foster through the proliferation of flex office spaces, informal gathering spaces, a church sanctuary rented out to secular events, and the capture of its congregants as social and spiritual beings in local and global evangelical efforts.

The surveillance cameras collapse the image of these adaptable spaces, designed to function as an image of freedom and flexibility, with a technique of imaging that appears to contradict this neoliberal ethos, actively performing threat assessment and policing these spaces.

Similarly, militarized nationalist displays, at the James River Church Stronger Men’s Conference and fourth of July I Love America Celebration contradict the global orientation of James River Church and the Assemblies of God as tax-exempt organizations with their own self-optimizing network and jurisdictions extending their global reach through mission trips to cultivate the “new generation of laborers.”

In Walled States Waning Sovereignty, Wendy Brown helps us understand that architectures of exclusion and policing as well as nationalist and theological intensification, are not contradictory to global aspirations. In fact, reactionary ideologies and infrastructures are often instrumentalized as appeals to the anxieties brought on by globalization. The megachurch acts as a point of confluence that reveals this interrelation—as a neoliberal architecture within a global network and as a reactionary infrastructure turning inward.